The snowstorm had been blowing all day and the aerodrome at Calshot, Hampshire had been in lock down most of the day. As the wind whipped the snow around the hangers, engineers were huddled around heaters trying to keep warm.

In the mess room Flight-Lieutenant Samuel Kinkead was talking with his close friend and fellow pilot Captain Henry Baird. As a former winner of the Schneider Trophy in 1922, Baird was perfectly placed to offer advice to ‘Kink’ as he was known to his friends in his attempt to break the world air speed record. Over cups of steaming hot tea they discussed the course and tactics needed.

The record had been set in previous year in November 1927 by the Italian aviator Major Di Bernardi, flying his Macchi M.52R racing seaplane to a record 297.817 mph. Now five months later the British and Flight-Lieutenant Kinkead were determined to break the record and prepare the Team for the 1929 Schneider Trophy due to be held at Calshot.

As the snowstorm continued to batter the aerodrome, the attempt was looking increasingly unlikely to take place, the engineers were trying to keep Kinkead’s Supermarine S.5 flight ready and the official timekeepers from the Royal Aero Club were losing patience. Baird did his best to keep his friend’s morale up but ‘Kink’ was getting frustrated and spiritless.

Kinkead being carried by his engineer to his aircraft prior to the test flight.

Samuel Kinkead was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1897 and joined the Royal Naval Air Service in September 1915 and had earned his wings by the end of the year. He was posted to 2 Wing RNAS who were sent to Gallipoli and within three weeks, while flying a Bristol Scout scored his first kill when he shot down a Fokker. He scored a further two kills while flying a Nieuport before contracting Malaria and being sent home to convalesce.

While in England he heard that his older brother had been killed in a flying accident as he trained for his wings but despite the news less than two weeks later he was posted to 1 Naval Squadron to fly Nieuports on the Western Front and within a month had scored two more kills to become an ace.

By the end of the war he had 33 confirmed kills and had been awarded Distinguished Service Cross (with bar) and Distinguished Flying Cross (with Bar). After the war he volunteered to serve with 47 Squadron and was sent to Russia to participate in the Civil War. In October 1919 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for a crucial ground attack against a Bolshevik cavalry division near Kotluban, thus saving the city of Tsaritsyn from capture. He also scored a further 3 kills before being posted home in 1921.

He one of the RAF’s most experienced pilot, he had taken part in the 1927 Schneider Trophy and despite having retired after five laps his third lap was the fastest ever recorded for a Biplane Seaplane. Now he was entrusted with beating the Italians and getting the World Speed record back.

At 4pm the weather finally broke and the sun broke over the aerodrome. While the sea was like a mill pond, the visibility wasn’t the greatest and Kinkead seemed undecided if to start but made a snap judgment and informed the Royal Aero Club that the attempt was to go ahead, the timekeepers came out from where they were keeping warm and took up their positions.

The engineers rolled out the Supermarine S.5 and as Kinkead climbed into the cockpit the late afternoon sunshine glistened of the monochrome bodywork. With a last check with his engineers, the engine roared into life and at ten minutes past five, Kinkead revved up the Napier Lion VIIB engine and took to the water.

Kinkead climbing into his Supermarine S.5. This picture was taken just 15 minutes before his crash and the RAF lost one of their best.

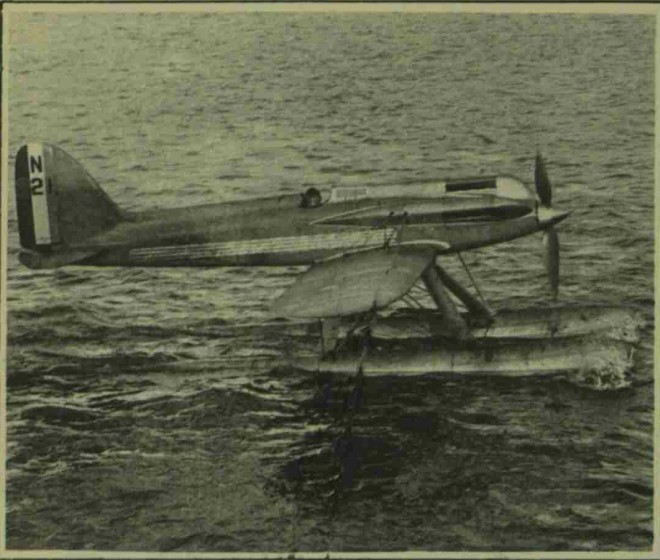

The Supermarine S.5 was designed by Reginald Mitchell for the 1927 Schneider Trophy and the S.5 featured composite construction with the semi-monochrome fuselage mainly duralumin including the engine cowlings. The S.5 had a low, braced wing with spruce spars and spuce-ply ribs and a plywood skin. Powered with a 875HP Napier Lion VIIB the planes had come first and second at the race held in Venice. These machines would become the precursor to the famous Spitfires.

Kinkead in his Supermarine Napier S.5 prior to take off.

As Kinkead taxied down the Solent he appeared to have some difficulties in rising and had to turn and skim across the water for a mile and a half before finally taking off. He flew for ten minutes, putting the plane through its paces. The sleek lines and powerful engine pushed Mitchell’s design through the air before Kinkead landed near Calshot lightship and prepared for his record attempt.

Kinkead in the cockpit of his Supermarine S,5

After a couple of minutes, Kinkead opened up the engine and the machine seemed to take off with less difficulty and it was soon circling above the snow covered Aerodrome. The crowds expectation grew as Kinkead swung down and started to enter the course. Almost immediately disaster overtook him, as he entered the first corner, the spectators reported that they heard that the engines seemed to be roaring at full throttle and the next second the machine dived absolutely vertically into the water at a great speed.

As groans and shouts of alarm went up from the crowd the machine smashed into the dark waters of the Solent and a column of water rose several feet into the air.

As a shocked silence descended on the crowd a high speed Air Ministry coastal boat raced to the scene but despite being there within two minutes, the machine and Flight Lieutenant Kinkead had sunk without a trace.

Despite crashing into relatively shallow water, it took the Navy two days to find the wreckage, The force of the impact had split the fuselage in half and it seemed that Kinkard had been thrown clear of the wreckage and his body was now at the bottom of the Solent.

The wreckage was taken to Calshot and the controls were laid out on the slipway to check for any technical fault but the inspectors could find nothing technically wrong with the machine. As the inspectors checked the main body of the craft they found Kinkead, minus half this head compressed into the tail unit and they had to cut the tail open to retrieve his body.

Flight-Lieutenant Samuel Kinkard DSC DFC DSO

Despite a RAF inquiry and a Coroner’s Inquest, neither were able to establish a definitive cause for the crash. Various theories have been put forward including either the mist and or the still water caused him to misjudge the turn, a relapse of the Malaria that left him feeling below par to even carbon monoxide poisoning, though the autopsy found no evidence of this.

Perhaps the last word is best left to D’Arcy Grieg the pilot who took over from Kinkead.

“Flying at over 300 MPH and at no higher than 150 feet ‘Kink’ was never more than half a heart beat from disaster.”

Flight-Lieutenant Samuel Kinkead was buried at All Saints Church Fawley. His Headstone reads:

In memory of Flight Lieutenant Samuel Marcus Kinkead DSO DSC DFC who, on 12 March 1928 while flying at Calshot, gave his life in an attempt to break the world’s speed record.

Pictures courtesy of Mike Stockbridge @Stockotrader

Sources:

The Yorkshire Post 13th March 1928

The Leeds Mercury 13th March 1928

The Sphere 17th March 1928

The Illustrated London News 17th March 1928.