On this day in 1913…The death of Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, KP, GCB, OM, GCMG, VD, PC.

Garnet Wolseley was one of the heroes of the British Army during the late 19th century. A career soldier, he saw action in some of the important campaigns of the 19th Century.

From an Ensign in the Crimea (1853-56) he rose through the army until he was appointed Commander in chief in 1895. He was considered such a safe pair of hands that the saying “everything’s all Sir Garnet” came to mean all is in order.

In the Crimea he fought in the trenches at the Siege of Sevastopol being wounded twice.

He then fought in the Mutiny (1857-58) seeing action at the Relief and capture of Lucknow and then the actions of Bari, Sarsi, Nawabganj, the capture of Faizabad, the passage of the Gumti and the action of Sultanpur. In the autumn and winter of 1858 he took part in the Baiswara, trans-Gogra and trans-Rapti campaigns ending with the complete suppression of the rebellion.

The Relief of Lucknow

Next up was the China (1860) He was present at the action at Sin-ho, the capture of Tang-ku, the storming of the Taku Forts,[5] the Occupation of Tientsin, the Battle of Pa-to-cheau and the entry into Beijing (during which the destruction of the Chinese Imperial Old Summer Palace was begun)

In 1861 he was sent to Canada and while there went to investigate the American Civil War. He was smuggled across the battle lines by Southern sympathisers and once in the South he met Generals Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, and Stonewall Jackson.

Once back in Canada he was active in the defeat of the Fenian raids from the United States and then commanded the expedition that established Canadian rule over the Northwest Territories and Manitoba.

The expedition was through some of the roughest terrain that Canada could throw that them but Wolseley’s attention to detail and supply arrangement meant that this was overcome with minimum losses to his forces. On his return to England he was knighted for his services.

By now Wolseley was the safe pair of hands that the British government needed to fight the various Imperial fires that needed putting out. He further enhanced this reputation during the expedition to Ashanti (1873).

Wolseley accepting the surrender of the Ashanti tribe

He arrived on the Gold Coast before the troops arrived and made all the arrangements to needed. He knew it was imperative that the campaign to defeat the Ashanti Tribes before the unhealthy season started and caused havoc with his European troops.

Due to his advance planning within two months of his European troops landing he had defeated the Ashanti in battle, advanced and captured the capital, accepted the surrender of the Ashanti King and then re-embarked his troops before the unhealthy season had began.

This campaign made him a household name in Britain. He received the thanks of both houses of Parliament and a grant of £25,000 was promoted to brevet major-general for distinguished service in the field on 1 April 1874.

The freedom of the city of London was conferred upon him with a sword of honour, and he was made honorary DCL of Oxford and LL.D of Cambridge universities. On his return home he was appointed inspector-general of auxiliary forces with effect from 1 April 1874; however, in consequence of the indigenous unrest in Natal, he was sent to that colony as governor and general-commanding on 24 February 1875.

He accepted a seat on the council of India in November 1876 and was promoted to the substantive rank of major-general on 1 October 1877. Having been promoted to brevet lieutenant-general on 25 March 1878, he went as high-commissioner to the newly acquired possession of Cyprus on 12 July 1878, and in the following year to South Africa to supersede Lord Chelmsford in command of the forces in the Zulu War, and as governor of Natal and the Transvaal and the High Commissioner of Southern Africa.

By the time he arrived in South Africa he found that the war was a good as over but he negotiated the final peace deal. He then served in the Transvaal and was promoted to Brevet General.

In 1882 he was promoted to Adjutant-General to the Forces and sent to Egypt to command British forces who where fighting the Urabi Revolt for Muhammad Ali and his successors.

with his usual thoroughness, he seized the Suez canal, moved his troops to Ismailia and after a very short campaign utterly defeated Urabi Pasha at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir, thereby suppressing yet another rebellion.

He had again proven that he a soldier of the highest order and he was promoted to full General, received the thanks of both houses for a second time and raised in the peerage to Baron Wolseley, of Cairo and of Wolseley in the County of Stafford.

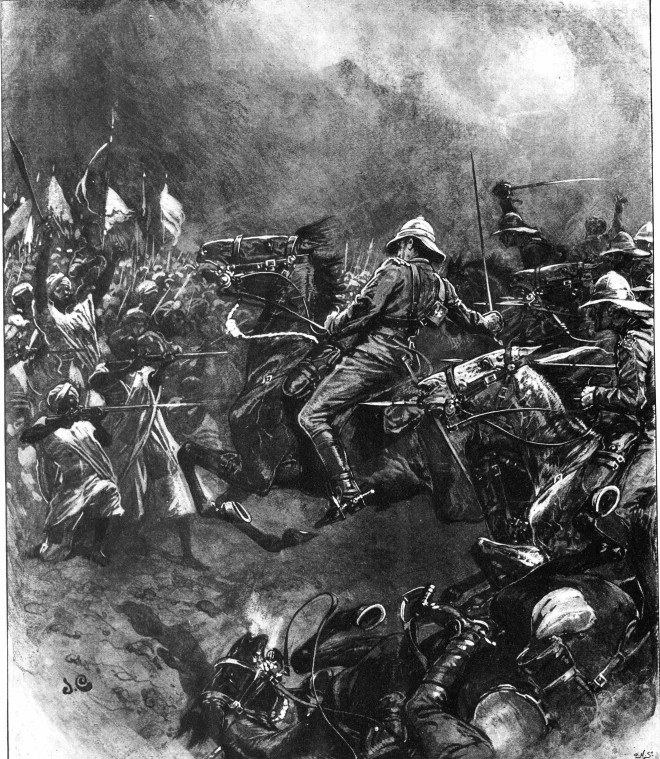

The Nile Expedition for the Relief of General Gordon, from The Graphic, 29 November_1894

In 1884 he was called way from his duties as adjutant-general to help save the Government’s reputation by leading a rescue attempt to save General Gordon at Khartoum.

He lead the expedition down the Nile with his usual excellence but due to delays in despatching the force by the time they arrived under the walls of Khartoum it had fallen and General Gordon was dead. Despite not being his fault it was the first failure of his career.

The expedition to Khartoum was to be his last active service and for the rest of his career his served at Horse Guards.

He was promoted to Field Marshal in 1894 and became Commander in Chief in 1895.

He was a favourite of the Royal Family and was appointed to Gold Stick to both Queen Victoria and Edward VII. He also took part in the procession at the funeral of Queen Victoria.

Happily married to Louisa he had just one child, Frances. For his service to the country, parliament made a special dispensation to allow Frances to inherit the viscountcy from her father.

Wolseley was a true hero of the Empire and fought across the globe for his Queen and country. In recognition of this a statue was erected in the Parade ground of Horse Guards.