The Battle of Maiwand was one of the principal battles of the 2nd Afghan War (1878-1880). A British force consisting of two Brigades of British and Indian troops under the command of Brigadier General Burrows (1827–1917) was defeated by an Afghan force under the leadership of Ayub Khan.

On the afternoon of 26 July information was received that the Afghan force was making for the Maiwand Pass a few miles away (half-dozen km). Burrows decided to move early the following day to break-up the Afghan advance guard.

As Afghan horsemen appeared the Burrows mistaken believed that they were the advance guard but it was Ayub Khan’s main force of 25,000 regular troops and five batteries of Artillery.

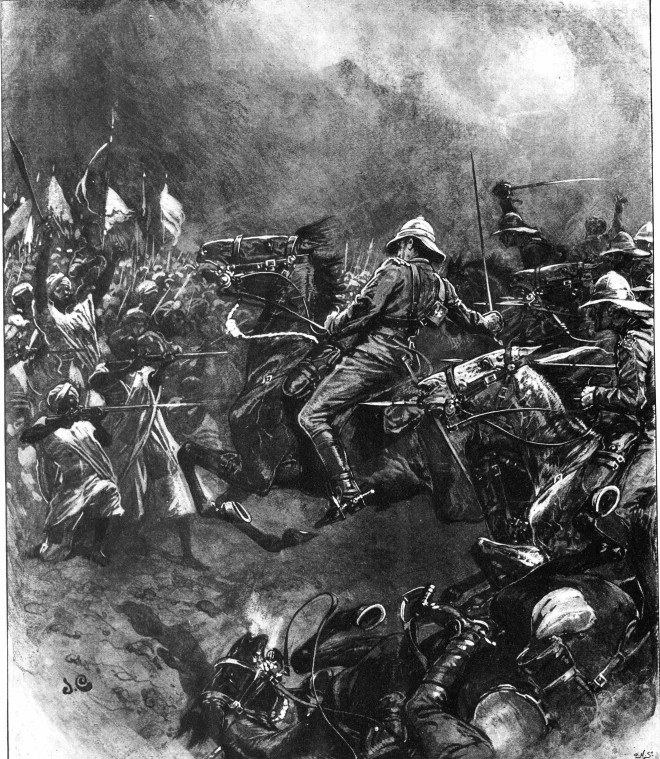

In the ensuing battle the British left flank, consisting of Indian regiments was rolled up and crashed into the British right and 66th Regiment was swept away.

Most of the regiment was caught up in the rout. Some 140 of them made a stand at the Mundabad Ravine, which ran along the south side of the battlefield, but were forced back with heavy losses. Eventually 56 survivors made it to the shelter of a walled garden and made a further stand. Eventually the 56 were whittled down to only 11 men—two officers and nine other ranks. An Afghan artillery officer described their end:

“These men charged from the shelter of a garden and died with their faces to the enemy, fighting to the death. So fierce was their charge, and so brave their actions, no Afghan dared to approach to cut them down. So, standing in the open, back to back, firing steadily, every shot counting, surrounded by thousands, these British soldiers died. It was not until the last man was shot down that the Afghans dared to advance on them. The behaviour of those last eleven was the wonder of all who saw it”

Queen Victoria awarding the Afghan War Medal to Bobbie the dog, survivor of the Battle of Maiwand, and other members of the 66th Foot at Osborne House

The British Force was routed but in part by the ferocious efforts of the British survivors and in part by apathy of the Afghans they managed to withdraw towards the relief force heading out from Kandahar. The British and Indian force lost 21 officers and 948 soldiers killed, and eight officers and 169 men were wounded and the 66th lost 62% of their strength. Its believed that the Afghans lost up to 3000 men.

A medical officer who was present describes the the battle and the retreat to Kandahar.

Candahar (sic) August 21

On the morning of the fight we made a march of seven miles to Maiwand for the sole purpose of attacking a force of 1000 Ghaisais (Afghan fanatics), who were said to have occupied the place; but when we got within two miles of Maiwand we came across the whole force of Ayoob Khan _ I suppose between 15,000 and 20,000 troops, with 30 guns, occupying a very strong position.

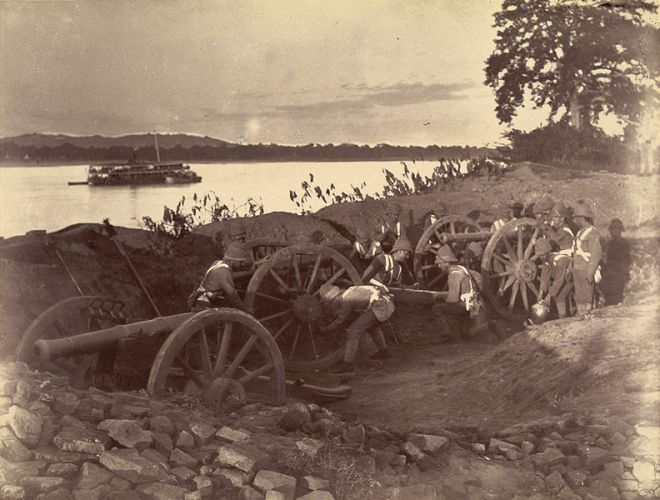

Our force was a little over 3,000 strong, with six guns of the Royal Horse Artillery and four guns we had taken from the mutinous army of Shere Ali at Giriakh. The order was given to attack at once. The battle commenced about 11am and there was hard fighting up to about three pm, when our two native infantry regiments broke. This caused the retirement of the 66th, who I hear, fought splendidly.

Afghan commanders after their victory at the Battle of Maiwand.

In the opinion of everyone all might yet have been well had the cavalry charged, but they refused to obey orders. They did not cover our retreat or protect the guns at all. The cavalry loss was very very small compared with the losses of all the other regiments and there is a very bitter feeling against them as they might have done so much to save the force.

When once the retreat commenced all the horrors of fighting savage nations began. Most of our wounded, poor fellows had to be left on the ground, and their fate, of course was sealed. It makes one’s blood run cold to think of the sad fate of such a number of gallant men.

That day we lost 20 officers killed and missing, and five were wounded, who I’m thankful to say, were all brought in here. The retreat from Maiwand to Candahar (sic) – close upon sixty miles – is an event that was never be forgotten by anyone who participated in it. We left Maiwand just a little after three pm and we reached Candahar at 3.30 pm on the following day.

During the whole of our march, up to within five miles of Candahar, there was not a drop of water to be obtained anywhere. This is one of the reasons why we lost so man men. They simply dropped on account of great thirst. In addition to this the inhabitants, of every village en route turned out and had shots at us. In fact many of the forces were under fire more or less, the whole way.

Lord Roberts (L), first Baron of Kandahar and Waterford and endeared to Tommy Atkins as ‘Bobs’ is one of our most distinguished Generals and established his fame in the Afghan War of 1880.

Our total loss was I believe :- 20 officers killed and missing, five wounded (and doing well) about 950, both native and European killed and missing, about 200 wounded, and about 550 camp followers killed and missing. Besides this the colours of the 66th and 1st Bombay native infantry were taken, and six guns- two of the Royal Horse Artillery, and the four we took from Shere Ali.

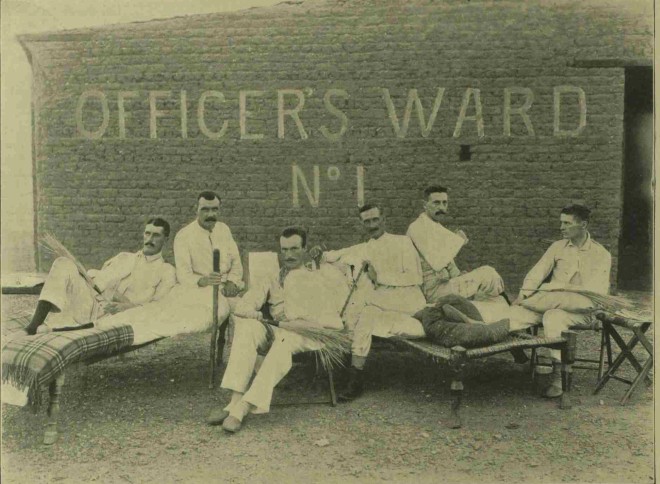

For a week before the battle I had been suffering badly from fever and was on the sick list, having been carried in a dooley on the 27th July. When the fight was going on I got upon my legs and tried to get a look at what was passing. I went to the rear and attended to one or two of the 66th who were wounded.

I soon found that our force kept retreating and at last the general retreat took place. All the dooley walis had bolted and there was nothing left for me to do but to walk, which I did, I suppose for about a mile. I could not find my horse although I had given strong instructions to my ayse to keep close to me..

All this time I was feeling far from well and most awfully faint. I had only had a cup of tea and a biscuit in the early morning. Luckily I managed to get hold of a mule, and on this animal I got into Candahar. How I ever got in here alive I do not know. I have much to be thankful for.

I used to have to get off the mule every two miles and lie down and have about ten minutes sleep. On these occasions I always managed to get hold of someone to stay by me to help me on the mule again, for to have mounted without help would have been an utter impossibility, considering how fearfully weak and exhausted I was.

How I got in will always be the greatest mystery to me, I lost all my kit, my horse and my salary. The first fortnight after this terrible affair I was laid up again with the fever.

Such a nice lot of officers have been taken away by this calamity – young fellows, mere boys, full of pluck. It is dreadfully sad and sickening when one thinks of how many good and valuable lives have been lost and of the number of homes that have been desolated.

If there had only been water on our road back from Maiwand we should not have lost one half of the men. It is very slow and dull work being boxed up in Candahar. The enemy have as yet made no assualt upon the place, and the general opinion is that they will not do so. Generals Roberts and Phayre must soon be up. It is astonishing how all the fellows keep up their spirits.

Part two is coming soon…